“You’re wrong,” is what I wanted to say. “You don’t give people a chance. You’re just a spoiled snobbish whining brat without the slightest concern for someone else’s problems.” That’s what I wanted to say. Instead I shook my head, grinned, and pretended to sympathize with the Irish girl—the ridiculous things she said.

In the cool departing daylight of late summer’s afternoon, seated outside at a corner café, I wanted it sweet. I was swirling my third cognac, getting ‘up to speed’ while Parisians flew past, allegro ma non troppo, moving like the Métro. I had dubbed this motion the Paris Sidewalk Surge. Even our café crowd raced, running a rapid chatter of demi-tasse and cigarette ash, making Paris al fresco like bathing with an immersed electrical appliance.

I sat with a young cousin who, for no valid reason, resented this stimulated city. Paris was such a drain upon her Irish Catholic colleen misty virtue, and you could be sure the Sisters never taught her ’bout the charging of the batteries. She could only sit, sparking static, dead in the water, turning her teaspoon blue. And I could only listen to complaints hiss forth like the painful escape of air from a balloon.

“Why is it that every time I’m waiting in line, someone steps in front of me? Yer man at the Berthillon, I swear, he almost pushed me over. I think he just wanted to put his hands on me…it’s like these people never heard of first come, first served.”

My mood blackened. It should have been sweet. Still I listened.

“…and it was so humiliating the way yer woman treated me, like I was an inconvenience because I wouldn’t speak French. Why do you have to speak French to buy a pair of shoes? It was a laugh to have her bring those boxes and leave without buying a thing. You should have seen the way she looked at me….”

No problem there. In the mind’s eye I saw the expression, but the mind’s eye blinked at a kind of interruption, not unusual, someone by our table. I was forced to say, “No, I’m not, I can’t give you an autograph…sorry. Have a nice day anyway.” The person left, a little embarrassed, maybe unconvinced that I was not the celebrity for whom they had mistaken me. Maggie shook her head and rolled her eyes. I grinned. The famous American film director disguise: baseball cap, sunglasses, and beard. Add the fact that I sat all confidence and impunity with a stunningly freckled strawberry blonde. It was so interesting to me—this counterfeit fame that made others approach. Maggie wouldn’t see it that way. An encounter outside her control, the impromptu brush with another life was to suffer a theft of distance: a dismal crime, a crack in the ice.

“Don’t you hate that? Having people stare at you, come up all the time, really, it would piss me off….”

I was about to tell her I liked it, it was fun, but that’s when a stranger leaned over to say, “You really do look like him.”

Maggie sighed.

I laughed. “Something I’m learning to live with.”

Why hadn’t I noticed the stranger sitting down next to us? This man was genuinely elegant—a rare quality these days. Suit with a vest and hightop leather shoes. Cravat and a Panama. It was well-worn class, charming and unexpected. His skin had the texture of nineteenth-century greasepaint. Character stubbled his cheek and jaw.

I found myself staring. Something about his features made me think of vintage nobility. Maybe his eyes, like an animated Dutch painting, glistening with alcoholic highlights yet penetrating and sure. Those eyes looked into mine. He saw me holding my breath. He smiled at that. He smiled and my perverse intuition sensed the show was just beginning. As his lips parted, a curtain pulled aside to reveal rotten, broken teeth, so shocking in the theater of his face. Maggie gasped.

“Excuse me,” she said, obviously upset. She rose bumping the table, escaping to what she hoped would be, in this precarious Paris, a safe toilette.

The man narrowed his eyes. “You’re not…really….”

A famous director? Holding my breath? “No, really, I’m not.”

“Of course you’re not.” He leaned back in his chair without taking his eyes from mine. Holding up a finger on a half-raised hand he invoked a waiter to appear miraculously. The elegant man whispered. The waiter, looking to the cap/the beard/the sunglasses, nodded then vanished into the chattering café.

The stranger kept staring at me. I wanted to break the awkward silence, but he spoke first.

“I’ve been here before.”

I nodded and mumbled, “Me too.”

He stared.

“Your English is very good,” I said.

“Your French is lousy,” he shot back.

Astonished I felt my face redden. “I don’t believe you’ve heard me speak French.”

“I don’t need to hear you speak…I can tell. Now…pay attention!” The last part he delivered like a slap. He cracked open a newspaper, hiding his face from view.

A moment passed. Two. What a bizarre exchange. A slight breeze made his newspaper tremble. Maybe he’s crazy. My finger swirled the top of my cognac glass. Suddenly, from somewhere deep within Le Monde, he spoke.

“Do you like Paris?”

“Yes, I….”

“Look across the street,” he said, cutting me short.

I looked.

“What do you see?”

“St. Germain-des-Prés…and some artists trying to sell their work and…” what the hell am I doing? ”…um, there’s a lot of people standing around, some of them are watching a mime, there’s also….”

“St. Germain-des-Prés…and some artists trying to sell their work and…” what the hell am I doing? ”…um, there’s a lot of people standing around, some of them are watching a mime, there’s also….”

“What is the mime doing?”

“Nothing, just standing there, frozen. People are putting coins in her hat….”

He cut me off again. “She’s a dancer, classically trained. Spent years at the barre. All she’s ever wanted from life was the freedom to dance, to move…and yet to live, to keep from starving, she makes her money by refusing to move.”

“Do you know her?”

“Across the street. Keep looking.”

I scanned the street and scaled the walls of the stony church with my eyes. Windows and window boxes. I caught a glimpse of movement then nothing more, so I looked back to the sidewalk. “There’s some person wearing a red and blue knit jumpsuit. He looks like a jester. He’s pulling tape off the fence.”

I waited. The elegant man replied.

“Oh, he thinks he’s Napoleon. The tape was left by artists who attach work there to sell. It makes Napoleon mad…they don’t clean up after themselves.”

This is really strange. He hasn’t looked up from his paper once. I felt an urgent need to get away. Break the spell. Instead I looked again across the street.

I saw something, or someone, that I had seen before. A man running. He was about thirty. He had a scrawny beard and a porkpie hat. His clothes were ratty, but only because they were old—probably old when he bought them. He carried a briefcase in one hand. His other hand dangled at his side. He ran at a trot. He didn’t smile. Wouldn’t smile. Never had smiled.

“He’s the Running Man,” said the voice behind the paper.

My voice was dry debris. “I’ve seen him before…in the Marais. He runs on the rue des Rosiers in the Jewish Quarter.” I looked toward the other voice, the one behind the paper. I wondered how he knew about the Running Man. I wondered how he could see him, buried in his paper. I wondered why his paper was upside down.

“How are you seeing that?” I asked.

“I’m not. I’m reading a newspaper…” He crushed it closed and dropped it onto the table, “…and it’s gotten dark.”

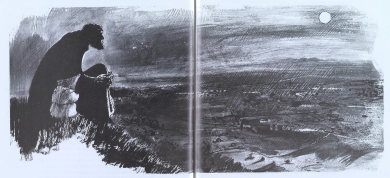

And it was dark, or almost was. The twilight that turns everything gray—city, street, buildings, people, the already gray pigeons that get even grayer. I blinked and his face was inches from mine.

“Pay attention,” he whispered with breath that smelled of every old book I’d ever read. “You won’t have to do much more than that.”

He turned his face to the stone-gray church, lost in thought or so it seemed, his eyes the color of something deep. He whispered, “There’s a moon tonight.”

Then he laughed and I almost pissed.

“Enjoy God’s Peep Show.” He stood up quickly, coffee unfinished, food untouched. He didn’t say goodbye—he was gone.

Maggie returned. “Oh, good, he’s gone. He was so weird.”

I remembered the special rush that comes after losing control of a car on ice.

“Let’s go,” she said. “Let’s go before he comes back.”

I made a move to signal the check and it arrived, miraculously. That is to say, they arrived. The checks.

“Excuse me,” I said in my, yes, lousy French. “There are two checks here.”

The waiter spoke conspicuous English. “The other gentleman said you would pay his bill as well.” The waiter stood waiting.

Maggie gasped, maybe spoke. I didn’t hear. I was looking across the street at that stony church, at its rows of blank dark windows. There was one window, underlined with geraniums, that had its curtains barely parted, revealing a room made dark by the dusk but not too dark to see the pink of flesh, the rosy priestly bottom backed against the glass—a holy moon. Black trousers rose to eclipse it then dropped again in a wicked game.

The curtains closed. I reached into my pocket and fumbled for coins. In spite of this double bill, in light of this double cross, I could only smile a new-found smile of absurd and frightening poetry.

“There’s a moon tonight.”

Trembling I reached to pay the checks.

“What are you doing?”

Shut up, Maggie, I’m paying attention.

© 1994 Craig Fleming